Introduction

The signing of the Rome General Peace Accords in 1992 signalled an end to Mozambique’s fifteen-year civil war and the start of the country’s formal transition to free market, neoliberal capitalism. In line with the privatisation and deregulation of the Mozambican economy, private art institutions such as Afritique and the Círculo Galería de Arte began to spring up, new exhibition spaces emerged at the Brazilian and French cultural centres, and a series of international art workshops were launched in Pemba and Maputo.[1] Profiting from the international exposure afforded them by this burgeoning contemporary art market, a group of eleven artists founded the collective Muvart (Movimento de Arte Contemporânea de Moçambique) and quickly made clear in a manifesto their desire to ‘go beyond the classic genres of sculpture and painting and include other materials and forms of representation’, as well as an attempt to ‘meet aesthetic standards as understood in an international contemporary art movement’.[2] The collective adopted the term ‘Arte Contemporânea’ to refer to this form of artistic practice, which is intended to indicate an aesthetic rather than a temporal category.[3]

Since their formation in 2002, both the aesthetic and practical implications of Muvart’s Arte Contemporânea have gone on to play a formative and all-encompassing role in the development of Mozambican contemporary art, setting a precedent which subsequent artists have invariably either built on or reacted against.[4] Vanessa Díaz Rivas has argued that Arte Contemporânea should be understood in a dual sense, as indicating both ‘an exploration of new forms of artistic production’ as well as a ‘rejection of the idea of an existing national canon’ and its ‘traditional’ forms of practice.[5] However, in spite of Díaz Rivas’ attempt to underscore a discontinuity of artistic paradigms in Mozambique, the work of Muvart and other Mozambican contemporary artists nevertheless bespeaks a persistent negotiation of themes and artistic genres that span a range of temporalities and historical periods, suggesting a practice defined more by continuity and coexistence than by any definitive break with the past. Taking Muvart’s paradigm of Arte Contemporânea as its point of departure, this article explores the coexistence of artistic paradigms in the work of Mozambican contemporary artists Gemuce and Félix Mula. As will be seen, this coexistence comprises a coming together of cultural forms from radically different social contexts, and is characterised above all by a process of ‘translatability’ that tracks patterns of interference across the cultural cartography of global capital.

Translatability and the ‘African Modern’

In their work on global African cities, Joseph-Achille Mbembe (known as Achille Mbembe) and Sarah Nuttall refer to the African experience of modernity as the ‘African modern’.[6] While the trajectory of capitalist development in Europe was long and drawn out, Mbembe and Nuttall point out that in many African societies this process was ‘compressed into under a century’.[7] The dizzying speed and velocity with which Africa as a whole experienced modernisation has in turn given rise to ‘a specific way of being in the world’ that has been ‘shaped in the crucible of colonialism and by the labour of race’, and that is palpable only as a host of ‘overlapping spaces and times’.[8] This African modern emerges at the intersection of a range of discordant temporalities, and should not be understood in contradistinction to pre-existing social relations. Rather, the African experience of modernity is combined and uneven, unfolding in a surreal juxtaposition of asynchronous orders and levels of historical experience, and describable as something like the uncanny impression of ‘time travel within the same space’.[9] In this context, past and present are not historically distinct or discontinuous, but two sides of the same coin; and it is to this extent that Mbembe has cautioned against arguments that reductively cast the modern as ‘a rejection of tradition’ or as mere ‘uprootedness’, advancing instead a definition that places the emphasis on sensibility.[10]

A typical feature of this negotiation between past and present is a process of ‘translatability’. As Stephen Shapiro and Neil Lazarus note, where ‘translation’ merely entails ‘the conversion or rendering of words, texts, concepts, etc. from one language to another’, translatability permits ‘the evaluation of how paradigms generated within one particular semio-ideological system might be transferred to another’.[11] The paradigmatic discourses associated with the project of modernity are manifold and always determined by asymmetrical distributions of power. In the African context, the transfer of paradigms – philosophical, political, cultural – attendant on the introduction of capitalist production processes by the European colonisers was made possible by a ‘mutual (but differentiated) location in a (world) system marked by imbalance, competition, violence, and the struggle for hegemony’.[12] This systematic oppression produced a process of translatability that generated new patterns of ‘interference’,[13] transforming cultural relations and enabling new forms of cultural production. As the agronomist and Marxist revolutionary Amílcar Cabral was wont to emphasise, ‘imperialist rule, with all its train of wretchedness, of pillage, of crime and of destruction of cultural values, was not just a negative reality’.[14] Aesthetic registrations of the African modern should then be seen to occupy a space in between the violent introduction of European epistemologies and local social relations, inhabiting a site in which past and present do not stand in sequential relation but exist in confluence and simultaneity.

Arte Contemporânea

When Díaz Rivas claims that ‘Muvart translated the category of “contemporary art”, defining it according to its own necessities, and creating a link to international expectations of what “contemporary art” should be’,[15] she therefore conveys only one side of the story. What goes missing in Díaz Rivas’ account are the ways in which Muvart artists incorporate pre-existing, local themes and artistic practices into their work, even as they make an explicit attempt to ‘move beyond’ them. Muvart’s definition of Arte Contemporânea as an aesthetic as opposed to a temporal category is crucial, for it actively resists the notion that contemporary art moves linearly and teleologically from ‘North’ to ‘South’ or from ‘West’ to ‘East’, opting instead for a form of practice in which ‘classic genres’ can coexist with new techniques or materials on a level, if uneven, playing field.

Translatability is here present in the transfer of artistic paradigms and the fusion of artistic forms. While the aesthetic agenda of Arte Contemporânea displays a marked emphasis on conceptual, video, and action art practices – traceable to the intrusion of global capital upon the local landscape of Mozambique and the ‘neoliberal turn’ of the early 1990s – there nevertheless persists a preoccupation with pre-existing themes and artistic genres that indexes the incommensurabilities and contradictory temporalities embodied in the concept of the African modern. A look at the work of two key practitioners of Arte Contemporânea confirms this preliminary observation.

Gemuce: ‘Swinging between Today and Yesterday’

As a founding member of Muvart, Gemuce’s work spans the full range and versatility of the collective’s artistic practice. Despite having trained as a painter in the figurative style of Soviet Realism, he was also experimenting with video and installations at a time when these media were virtually unheard of in Mozambique.[16] Painting has nevertheless remained a core part of Gemuce’s work, and even while it amounts to a ‘classic genre’ in Muvart’s terms, he manages to infuse it with much of the collective’s contemporary-mindedness in his experiments with both form and content.

In his painting series A Tale of One City (2009),[17] we find people of varying ages and appearances swinging back and forth among the clouds in a clear blue sky. Combining a realistic painterly style with the notably unrealistic notion of swings in the sky, these paintings seem to uproot their subjects from concrete historical reality and place them in a free-floating non-place where the only textual markers that would serve to locate the depictions are the loaded catchwords tagged to the corners of the canvasses: ‘Authority’, ‘Competition’, ‘A friend’. While the lack of spatio-temporal reference points would at first glance appear to take up the deterritorialised notion of a ‘global village’, a closer look reveals these paintings to be more fundamentally inscribed with the social conditions of a Mozambican reality.

Gemuce, series: A Tale of One City, 2009, oil on canvas, 150 x 120. From: Vanessa Díaz Rivas, ‘Contemporary Art in Mozambique: Reshaping Artistic National Canons’, Critical Interventions 8, no. 2 (2014): 168.

Gemuce, series: A Tale of One City, 2009, oil on canvas, 150 x 120. From: Vanessa Díaz Rivas, ‘Contemporary Art in Mozambique: Reshaping Artistic National Canons’, Critical Interventions 8, no. 2 (2014): 168.The title of the painting series is a reference to Charles Dickens’ novel A Tale of Two Cities (1859), and was intended to draw parallels between Dickens’ story of political turmoil and recent periods of unrest in Maputo.[18] Indeed, it is not hard to appreciate why a story of antagonistic class relations, of aristocratic rule over a subjugated peasantry, of popular uprising and the ultimate corruption of successful revolutionaries, would begin to appeal to the contemporary situation in Mozambique, even when the contexts are as historically disparate as eighteenth-century France and twenty-first century Maputo. The switch from the plural to the singular in the title of Gemuce’s painting series can then be seen to index the spatio-temporal compression of globalised modernity, while Gemuce’s historical comparison also roots his paintings’ subjects firmly in the social unrest of modern-day Mozambique. In Díaz Rivas’ words, these paintings ‘all have in common this swinging between today and yesterday, tradition and modernity, Africa and Europe, and so on’.[19] Insofar as Gemuce’s painting series reaches across disparate historical periods, occupying at once realist and irrealist artistic registers, it serves as an index for the dizzying effects of the African modern and unveils a process of translatability at work beneath its aesthetic operation.

As Derek Boothman points out, ‘[t]ranslatability presupposes that a given stage of civilization has a “basically” identical cultural expression, even if its language is historically different’.[20] In A Tale of One City, we find just such a presupposition as two historically different cultural expressions are brought together into a single aesthetic act in order to highlight a continuity of forms of capitalist oppression. Furthermore, insofar as a geo-culturally remote past is brought to bear on social relations in modern-day Maputo, we are reminded of Shapiro and Lazarus’ statement that ‘[t]he geography of translatability is the cultural topography of the capitalist world-system’.[21]

Félix Mula: ‘Other Orders of Visibility’

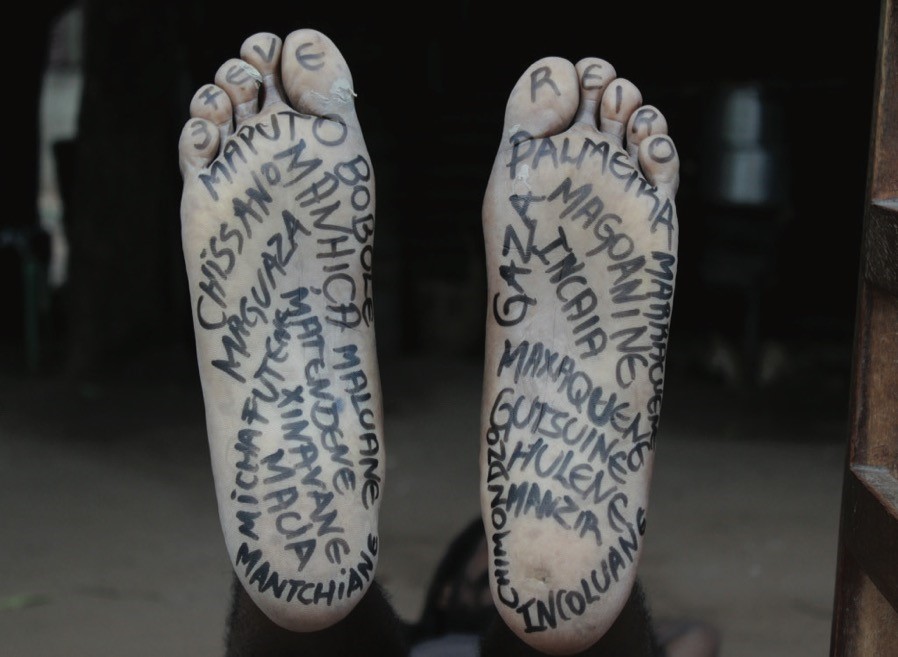

Félix Mula is a Maputo-based Mozambican artist who completed his Fine Arts degree on the island of Réunion in 2011. His work explores themes such as the history of labour migration in southern Africa and the overlap between individual and collective histories.[22] In a recent conceptual and action-based work, he travelled on foot from Maputo to Gutsuine near the district of Xai-Xai, equipped with only a small backpack, his mobile phone and a camera. The near 200 km journey took him six days, during which time he relied on the charity of others for both his food and accommodation. The concept behind the project, as Díaz Rivas explains, ‘was to revive, at least in part, the 800 km trip that his grandfather had taken once and sometimes twice a year between Durban […] and Xai-Xai’.[23] Like many other Mozambicans, Mula’s grandfather worked throughout the year in South Africa and, due to a lack of funds, was forced to make this journey on foot. In the late colonial period, the southern regions of Mozambique effectively functioned as a cheap labour pool for South African mining companies who exploited their workers with low wages and a total disregard for the tortuous cross-border journeys they were forced to make.[24] Mula’s work investigates this historical process both at the collective and individual levels, as the general history of colonial-industrialist exploitation is given a more concrete specificity through the personal memories of his grandfather.

The personal significance of his work is then further complexified as we learn that Mula himself was contracted for (illegal) migrant work in 1993.[25] Mula’s project thus cuts across historical periods to expose common and recurrent patterns of exploitation. And to this extent, the themes of displacement and vagrancy in Walking Maputo – Xai-Xai (2011)[26] might also offer an equally powerful registration of the abolition of communal land tenure and large-scale expropriation that accompanied structural adjustment in Mozambique during the 1990s.[27] Mula’s subject – the black migrant worker – is a suitable means of exploring these themes seeing as it throws into relief what Nuttall and Mbembe call the ‘other orders of visibility’ underpinning the African experience of modernity, thereby drawing attention to those concealed by informal or casualised economies and those more broadly excluded from the local acceleration of capitalist modernity.[28]

Félix Mula, Walking Maputo – Xai-Xai, 2011. From: Rafael Mouzinho, ‘Localizar e Deslocalizar a Arte em Moçambique: A Partir da África de Sul e de Portugal’, Third Text Africa 5 (2018): 154.

Félix Mula, Walking Maputo – Xai-Xai, 2011. From: Rafael Mouzinho, ‘Localizar e Deslocalizar a Arte em Moçambique: A Partir da África de Sul e de Portugal’, Third Text Africa 5 (2018): 154.Using a non-formal, conceptual medium in order to explore local themes inseparable from the economic development of southern Africa, Mula overlays individual and collective histories from distinct, yet structurally similar epochs. While this ‘overlapping of spaces and times’ corresponds to the perceivable effects of the African modern, his work also acknowledges the centrality of pre-colonial oral traditions to local epistemologies in southern Africa. As Díaz Rivas explains, although Mula documented his walk with photos and videos, ‘the work of art consists primarily in the narration of his walk […] [h]e wanted people to hear about his walk to Gutsuine as he heard from his grandmother and father about the walks of his grandfather; his actions remained incomplete until he gave his story to others’.[29] In this way, the Walking Maputo – Xai-Xai project directs us back to the notion of regimes of visibility, with the artistic quality of Mula’s work residing primarily in its oral dimension as opposed to its visual documentation. The conceptual medium with which Mula decided to stage this juxtaposition of temporally distinct cultural forms further indicates a type of cultural interference inasmuch as it deploys a Euro-American artistic paradigm – first championed in Mozambique by Muvart during their formal experimentation of the early 2000s – and transfers it to the local environment by imbuing it with local themes and epistemologies. The result is a swinging between today and yesterday, Africa and Europe, much like the oscillating effect of Gemuce’s painting series.

Conclusion

The works of these two artists describe a form of contemporary artistic practice in which past and present are not temporally disjunct but experienced simultaneously and in direct correspondence with capitalism’s ‘complex and differential temporality’.[30] In Gemuce’s A Tale of One City we find a fusion of historically different cultural expressions that speak to the overlapping temporalities of the African modern in a ‘classic’ artistic medium. Likewise, in his conceptual work Walking Maputo – Xai-Xai, Mula uses a Euro-American aesthetic vocabulary and imbues it with local histories and epistemologies, telescoping the past and the present into a single aesthetic operation. In light of these readings, Díaz Rivas’ argument that ‘Muvart’s contemporary artist seeks […] a total break with the past, encouraging an art that lives in the “contemporary”,[31] appears misleading for two reasons. First, it presumes that contemporary art in Mozambique was only brought into being through the importation of Euro-American artistic practices and that the local artistic landscape could therefore only attain the status of ‘contemporary’ by way of contact with Euro-American social practices. Second, her definition of ‘contemporary’ is fundamentally at odds with the African experience of modernity, seeing as it suggests a linear progression from past to present that ignores the temporally discordant nature of the capitalisation process. Reflecting on the meaning of the ‘contemporary’ in the field of cultural production, Pierre Bourdieu acknowledged that ‘[t]he field of the present is merely another name for the field of struggle’.[32] In the case of Mozambique and Arte Contemporânea, we can say that the formal and conceptual experimentation pioneered by Muvart in the early 2000s did not erase previous artistic practices or preclude an engagement with local paradigms but was rather forcibly conjoined with these pre-existing cultural relations in a contested space defined by struggle. Any reading of Mozambican contemporary art must take into account the ways in which this coexistence of temporalities is registered in artistic form.

Bibliography

Abrahamsson, Hans and Anders Nilsson. Mozambique: The Troubled Transition: From Socialist Construction to Free Market Capitalism. London, New Jersey: Zed Books, 1995.

Anderson, Perry. ‘Modernity and Revolution’. New Left Review 144, no. 1 (1984): 96–113.

Boothman, Derek. ‘Translation and Translatability: Renewal of the Marxist Paradigm’. In Gramsci, Language, and Translation, edited by Peter Ives and Rocco Lacorte, 107–134. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure in the Literary Field. Translated by Susan Emanuel. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996.

Cabral, Amílcar. Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of Amílcar Cabral. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973.

Costa, Alda. ‘Artists of Mozambique: Looking at Themselves and at their World’. Third Text Africa 5 (2018): 4–26.

Díaz Rivas, Vanessa. ‘Movimento de Arte Contemporânea de Moçambique – Defining Borders, Creating New Spaces’. In New Spaces for Negotiating Art and Histories in Africa, edited by Kirsten Pinther, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nwezi, and Berit Fischer, 72–91. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2015.

— ‘Contemporary Art in Mozambique: Reshaping Artistic National Canons’. Critical Interventions 8, no. 2 (2014): 160–175.

Federici, Silvia. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012.

Mbembe, Joseph-Achille. ‘Aesthetics of Superfluity’. In Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis, edited by Sarah Nuttall and Joseph-Achille Mbembe, 37–67. Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2008.

Mouzinho, Rafael. ‘Localizar e Deslocalizar a Arte em Moçambique: A Partir da África de Sul e de Portugal’. Third Text Africa 5 (2018): 150–158.

Nuttall, Sarah and Joseph-Achille Mbembe, eds., ‘Introduction: Afropolis’. In Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis, 1–33. Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2008.

Shapiro, Stephen and Neil Lazarus. ‘Translatability, Combined Unevenness, and World Literature in Antonio Gramsci’. Mediations 32, no. 1 (2018): 1–36.

Silva, Bisi, Marianne Hultman and Daniella van Dijk-Wennberg. ‘Maputo: A Tale of One City’. Third Text Africa 5 (2018): 122–131.

Warwick Research Collective (WReC). Combined and Uneven Development: Towards a New Theory of World-Literature. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015.