Damian Lentini: Let’s start by talking about two projects, which are taking place concurrently in 2020 – ‘Zugzwang’ at Haus der Kunst, and ‘In Cold Print’ at Nottingham Contemporary – and the way in which you thought about these commissions.

Sung Tieu: At Haus der Kunst, my initial desire was to propose something derived from personal experience. ‘Zugzwang’ is autobiographical in a way, but it’s also tangential, told through bureaucratic forms, from the perspective of fictional characters. I’m looking through the lens of paperwork, mostly, and the ways they have formulated parts of my being. The sculptures, objects, texts, and sounds attempt to open up a psychically charged space between the personal and something culturally far more universal, something everyone can relate to.

In Nottingham, the show departed from my previous research into Ghost Tape No. 10, which was the name of a sound weapon developed by Psychological Operations of the US Army at the end of the 1960s in Saigon, and which I also like to call ‘the ghost of the American psyche’. We collaborated with scientists from Nottingham Trent University in order to find out about sound frequencies, how they travel through the body and through architectural space. One focus was the ‘Havana Syndrome’, which I first read about in the news and found an immediate connection to my previous research into psychological warfare, their histories and contemporary resonance. This so-called syndrome consists of a set of symptoms, such as headaches, hearing loss, and nausea, which were reportedly experienced by US embassy staff based in Havana. The US government declared Cuba responsible for perpetrating the alleged ‘sonic attacks’ that caused these symptoms. This mysterious case raises relevant questions not only about post-Cold War relations between the US and Cuba, but also about the role of science versus conspiracy, and how longstanding political prejudices can be weaponised. I also wanted to know how that data could be manipulated to convey certain political narratives.

DL: You speak of this intermingling of the autobiographical within your research into various structures – administrative as well as militaristic – and the superstructures that inform them. I would say that a third component, which manifests in both shows, is concerned with the history of modern art and design. How does this strand of your research come into play?

ST: I have been looking into the history of Minimalist art and design because there is something about it that I am intuitively skeptical about: its supposedly neutral forms. To me, these design choices communicate certain inscribed values and speak of larger social imaginaries even though their simplicity appears devoid of signifiers. For instance, the furniture I use, originally fabricated for the prison-industrial complex, is designed to comply with government regulations safety-wise but is also devised with a certain skepticism towards their users; in this case, prisoners. The similarities between Minimalist design and this state-imposed furniture are striking.

Another relationship I have been preoccupied with lies between the dematerialised art object and the war in Vietnam. Lucy Lippard notes that the era of Conceptual Art is also the era of the war in Vietnam and the Civil Rights Movement. The influential ‘Primary Structures’ show at the Jewish Museum in New York from 1966 comes to mind, but also Conceptual Art’s proposal to prioritise art as idea or action. What we have nowadays might be understood as a form of ‘Governmental Conceptualism’, seeking the withdrawal of exactly that: idea and action. It stands in total contrast to the 1960s ethos. Working towards ‘In Cold Print’, we came across another idea Victoria Hattam proposed: that one could think of Minimalism as a form of American cultural imperialism.

DL: A form of aesthetic imperialism, so to speak?

Cédric Fauq: Which particularly manifests through grid patterns.

ST: The grid reveals aesthetic affinities between a broad spectrum of disciplines and sites. For ‘In Cold Print’, we researched helicopter landing mats that were produced during the war in Vietnam to land heavy vehicles under monsoonal conditions. What is so fascinating about these landing mats is their design. They are essentially made out of corrugated steel arranged in grids. The idea was to make them sturdy and yet as flexible as possible for transportation. If you look closely at the grid patterns, you will find echoes of Sol LeWitt and Agnes Martin’s works.

Later, after the war, these M8A1 landing mats were repurposed by the Army Corps of Engineers to build large sections of the border fences between the US and Mexico, cost-free. So something that had a horizontal orientation, lying flat on the ground, was then turned vertical. The landing mat itself is a grid, with a horizontal and vertical axis. What does it mean to use that same grid to land on foreign territory you attempted to occupy and then repurpose it as fence to protect your own borders? There is a direct connection between the physical and psychic architecture of war and the wall.

CF: Another motif that appears in both exhibitions is the use of stainless steel, and more generally, mirrored surfaces.

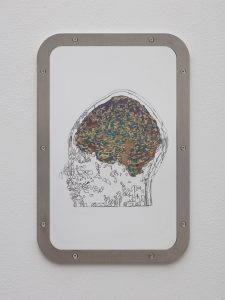

ST: In Munich, large stainless-steel mirrors are engraved with a digital rendering of a forest border between the Czech Republic and Germany. The mirroring at Haus der Kunst was inspired by visitation rooms in correctional facilities. Similarly, at Nottingham Contemporary viewers encounter themselves in six prison mirrors, overlaid by scans of my brain taken while being subjected to a recreation of the ‘Havana Syndrome’ sound weapon. Simultaneously, the audience is exposed to this same sonic attack through my sound work while walking through the exhibition.

DL: It would be great to hear about the way you worked with the sound components.

ST: At Haus der Kunst, we made new instruments based on office noise. I used Wagner’s overture to Tannhäuser (1845) and filtered its score through these office sounds. In order to do that, we had to devise an instrument for each noise. Then these instruments were fed back into Wagner’s composition.

CF: Did you use recorded sounds and then change their frequencies to match the score?

ST: Yes, which works better in some instances than in others. That’s very much part of the sound work: to try and live up to something like a Wagnerian ‘masterpiece’ – something cultural convention perceives as high art – but actually intending to force its collapse, its destabilisation, its breakdown into parody, twisting it and asserting one’s own ideas onto it.

CF: It’s interesting to think about it in relation to how diplomacy plays out and to the reconstitution of a sound weapon as noise music.

ST: I was eager to understand the witness accounts of the US diplomats, what they actually heard. What constituted the ‘weapon’ essentially. We then found a reconstruction of the sonic attack released by the US government based on witness descriptions. Bizarrely, it resulted in a high-pitched cricket sound. That’s exactly how it was described by a US official in a video clip we found.

To me, the ‘Havana Syndrome’ is less of a sound weapon than its psychological imagination: a sort of collective hallucination. It’s partly a psychological fiction and yet it inflicted real pain. The US Foreign Relations Subcommittee tried to find proof of its existence. But how do you find evidence of something so intangible, and secondly: How do you scientifically manifest that in order to leverage it as a fact? There is a cognitive dissonance inherent within the process of finding proof of an invisible threat.

One of the sound channels in ‘In Cold Print’ is the ‘original’ high-pitched cricket sound – the recreation of the ‘Havana Syndrome’ so to speak. Another channel plays my brainwaves responding to that recording, and the third layer is a composition of sounds based upon all the written descriptions of the sonic attack that I collected. So, you have these various ways in which the sonic attack has been psychologically or physically experienced through a collective body as well as my own.

DL: The use of sound to engender a physical response winds back very nicely to an idea underpinning Wagner’s conception of the Gesamtkunstwerk. [For him], ‘music dramas’ were environments whose sounds sought to elicit an active response from the audience.

ST: And we also know that classical music was used during the war in Vietnam as a form of weaponry, broadcast through loudspeakers mounted on helicopters.

CF: In your sound installations however, the speakers are concealed. Can you speak about your approach to how sound is installed and spatialised?

ST: What’s most appealing about sound is its omnipresence. You don’t need to see it in order for it to occupy your mind. In pretty much all of my installations, the sound source remains untraceable, to an extent, uncertain. I enjoy how much confusion this creates for people who haven’t visited my exhibitions in person but experience them online or via images. They miss the main work and, since I provide as much visual material as sound, they don’t seem to notice it. It goes unregistered … as intended.

This abridged conversation is excerpted from Sung Tieu: Oath Against Minimalism (forthcoming, 2020), published on the occasion of the artist’s solo exhibitions ‘In Cold Print’ at Nottingham Contemporary and ‘Zugzwang’ at Haus der Kunst, Munich. A public dialogue between the artist and curators was due to take place at Nottingham Contemporary on April 25, 2020 as part of ‘Acousmatic Paranoia’, an afternoon of talks and performances expanding on Sung Tieu’s artistic practice by AUDINT members, Hyperdub founder Steve Goodman (Kode9), media scholar Toby Heys, and media theorist and sound artist Eleni Ikon, which can be read in this special issue.